IT’S CRUNCH TIME here in Massachusetts for big brown bats (Eptesicus fuscus) as they get in their last few nights to hunt for bugs before settling in for the long winter. Named for their foot-wide wing span, big brown bats curl up to the size of a mouse. Shy around humans and deeply social with their own kind, they prefer to return each winter to the comforts of the same hibernaculum—or hibernation spot—and the company of the same fellow bats.

We’re unlikely to get another glimpse of them until sometime in April, when they’ll emerge in the gloaming, thin and hungry, and return to their nightly hunts. If we’re lucky, my neighbors and I will spot them swooping over our yards and around streetlights as they zero in on their prey. Their trademark herky-jerky way of flying helps us distinguish them from birds like swifts and starlings. Each bat will, stunningly, gobble up as many as a thousand insects a night.

Big brown bats are the most common bat in Massachusetts and the species best adapted to co-exist with us. Elise Stanmyer, a Massachusetts biologist and bat expert, calls them, with affection, the “pigeons of the bat world.” They’re living quietly all around my densely settled Northampton neighborhood. For hibernation, they prefer any dark place with consistent temperatures and humidity: under the eaves of houses and garages, in chimneys, between walls, in the cupolas and lofts of old barns, in the dead trees—or snags—in the woods that border our street. Once situated, their body temperatures will drop and their breathing and heartbeats will slow. They enter a state of torpor.

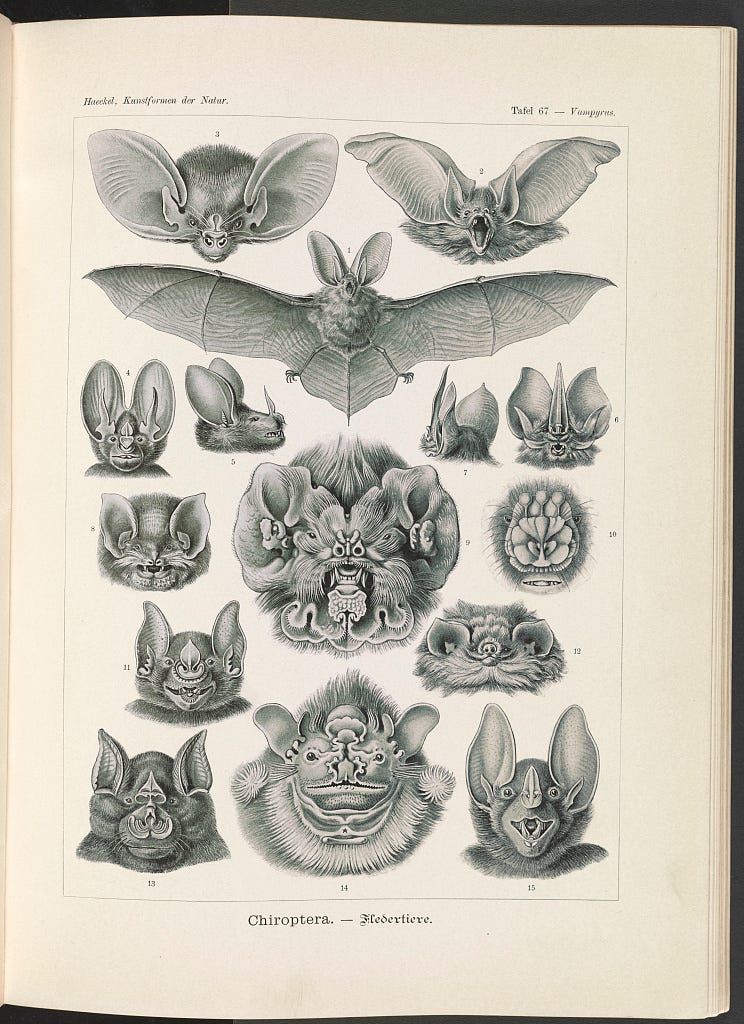

There are 1,400+ bat species across every continent except Antarctica, representing a staggering 20% of our extant mammal species. Big brown bats are one of nine, all insectivores, who live in Massachusetts. They break down into “cave bats” and “tree bats.” Cave bats, like big brown bats, hibernate in caves or cave-like structures. Western Massachusetts doesn’t have many caves, but its abandoned mica, emery, and granite mines have been critical stand-ins, supporting large colonies of different species of cave bats for decades. Tree bats, who like to hang out in…trees, are generally bigger and capable of flying higher. Instead of hibernating, they migrate each fall to the coast or a couple hundred miles south for the warmer temperatures. My favorite is the hoary bat. Solitary and large, they hang upside-down among tree branches, well camouflaged, with their furry tails wrapped around their bodies like sleeping bags.

For a host of reasons, all human-related, five of these nine bats are now on the state’s endangered list.

MANY OF THE ANIMALS who live side by side with us have suffered historically from persecution—think snakes, spiders, and crows—but none have lived under a cloud of nonsense quite like the bat.

Myth: Bats are blind. Truth: Depending on the species, they see as well, or better, than we do.

Myth: Bats get tangled in people’s hair. Truth: That’s not a thing.

Myth: Bats want to suck your blood. Truth: Only three species in the world are vampire bats and all are “microbats.” They live south of the Mexican border and lick blood from incisions they make on sleeping birds and mammals.

Myth: All bats have rabies. Truth: About .5 percent of bats carry rabies.

Myth: Bats are mice with wings. Truth: Bats aren’t even rodents. Genetically, they’re much more closely related to us.

As long as there have been humans, we’ve been dividing animals into good or evil. Because bats are mysterious to us—nocturnal, elusive, and the only mammals who fly—we’ve feared and loathed them almost universally. A bat in your house, according to much folklore, is a sign that death will visit soon. Throughout literature, they’ve been harbingers of death and colluders with witches and devils. In Dante’s Inferno (Italy, 1321), for example, Satan has three faces with bat wings protruding from each of his three chins.

Vampire mythologies go back as far as ancient Greece and Rome, but the association between bats and vampires wasn’t made until the nineteenth century. It was sparked in part by Charles Darwin’s account of witnessing a vampire bat—so named for the monster—feeding off a horse’s withers in Chile. Soon, Victorians were scooping up Varney the Vampire (1845-1847), a penny dreadful, which established many of the now-familiar vampire tropes, like fangs and superhuman strength. More gothic horror followed, but no story was as enduring as Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which was first published in 1897.

THANKS TO WILDLIFE BIOLOGISTS and animal welfare groups, bats have undergone a major rebranding over the last few decades, from a devil with wings to nature’s superhero. Their contributions to the environment—many directly benefitting humans—are too large to measure. The seeds they drop in clear-cut rainforests contribute up to 95% of the first new growth. They spread seeds for crops like cacao and figs. They pollinate bananas, avocados, mangoes, and agave (the ingredient in tequila). Their nitrogen-rich manure—guano—has been used for thousands of years as fertilizer. They eat mosquitoes. They eat the insects that eat crops, saving farmers an average of $23 billion a year in the U.S. alone. Our local big brown bats, for their part, have a huge appetite for local crop pests like cucumber beetles, June bugs, and leafhoppers.

Many factors have contributed to the enormous challenges facing bats in Massachusetts, and elsewhere. Some are obvious, like habitat and biodiversity loss, pesticides that reduce insect populations, and climate change, which produces killer storms, extreme conditions, and disruptions to the seasonal norms. Some threats are less obvious, like wind turbines, which kill hundreds of thousands of curious bats in the U.S. each year when they fly into the blades. (Wind turbines are also responsible for killing millions of migrating birds who collide with them at night.)

Then came white-nose syndrome (WNS), first discovered in a cave in New York in 2006. The fast-spreading fungal spore, introduced from Europe, thrives in damp and crowded spaces like caves. It has already killed millions of hibernating bats in the U.S. Often noticed first as white fuzz on a bat’s nose, WNS causes discomfort and damages bats’ wings, forcing its host to move around and burn crucial fat reserves. Eventually, it causes starvation. Once the most common bat in Massachusetts, the little brown bat has declined 99% statewide because of WNS. In one local example: an abandoned mine in Chester was home in the fall of 2008 to about 10,000 little brown bats; by spring 2009, only 14 had survived. The little brown bat now joins 11 other bats in North America confirmed to carry the disease.

BIG BROWN BATS contract WNS, too, but fortunately, most of them prefer hibernacula that are too dry for the white fungus to thrive. So far, this has been a lifesaver. Conservationists consider them a “species of least concern” globally, though that phrase is a bit of a misnomer: biologists are carefully monitoring their populations because, like all bats, they are contending with multiple threats.

In the fall, right before hibernation, big brown bats breed then—here’s a trick—the mother bats delay fertilization, storing sperm in their uteri until they ovulate in the spring. Once out of hibernation, they will hunt exhaustively—eating up to their own weight in bugs each night—and join a maternity roost with other mother bats. In the Northeast, they tend to give birth to twin pups (further west, they’re more likely to have just one). The pups will begin nursing immediately and, for the first few days, will cling to their mother’s breast while she heads out on her nightly hunts. After about a month, the pups will start to take short flights on their own.

Big brown bats have good eyesight and rely on it for long-distance navigating. For short-term navigation, including locating insects, they use echolocation, emitting a series of supersonic cries through their mouths and noses. The echoes that come back help them locate objects, including beetles. They use their wing membranes to trap their prey, then pull them up to their mouths. This feat accounts for what sometimes looks to us like a less than balletic flight pattern.

Bat mortality in the first year is high. Pups are vulnerable to being captured by snakes, owls, and house cats, and they often can’t store enough fat for a whole winter. Those who do survive, though, often have an unusually long lifespan for a small mammal—about six years. Some, remarkably, have been tracked in the wild over the course of 19 years.

IT’S ILLEGAL IN THE STATE of Massachusetts to harm or harass a bat. Twice over the years, one has gotten into our house where we have a brief mutual freak out. I’ve then had good luck with this tactic: close the bat in a room, open the windows wide, turn out the lights, and leave. If you have a more complicated problem, like multiple bats in your attic, there are good resources out there for you. Because extermination is not an option, the standard approach to managing bats in your home is exclusion. That is, making it too difficult for bats to get in, while—through a one-way door—making it easy for them to get out. The timing for exclusion is essential, since maternal roosts can’t be disturbed.

If you’re a property owner, there are lots of things you can do to protect bats, as well as other threatened species like songbirds. Limit the percentage of your yard dedicated to traditional lawn and increase the percentage of native plants, which support insects. Never use pesticides. “Leave the leaves” and don’t prune back plants in the fall so insects have a hiding place to overwinter. Keep cats in the house.

A lot of my neighbors are starting to adopt many of these practices, creating little wildlife corridors. This past summer many of us thought we noticed more butterflies, moths, bees, and other insects than in previous years. For yard chores this month, instead of raking leaves, my husband and I are redistributing them around the garden beds. It’s a natural look I’m quickly growing fond of.

BAT MARGINALIA

In the stranger than fiction category, President Roosevelt green-lit a macabre experiment in 1942 to attach tiny napalm balms to Mexican free-tailed bats. The idea was to drop the bats over Japan, where they would—as would be natural for them—seek shelter, only to set buildings on fire. The engineers had success creating a workable model, but the project was soon eclipsed by the development of the atom bomb.

The connection between bats and insanity—see batty and batshit crazy—derives from the expression “bats in the belfry” which first appeared around 1899. The belfry is the mind, of course, and the bats are crazy thoughts. The painter James Whistler said of the French illustrator Gustave Doré: “Doré—yes, I knew him—he had bats in his belfry!” Whistler may have been making a joke, as Doré frequently used bats as a motif.

In 2015, the podcast Invisibilia ran a short series called How to Become Batman about a man named Daniel Kish. Blind since he was 13 months old, and a kid full of fearless energy, Kish developed a form of echolocation that he now teaches to other vision-impaired people.

The Bat-Poet by Randall Jarrell is a classic crossover book—appealing to both children and adults—illustrated by the master, Maurice Sendak. “A bat is born/Naked and blind and pale./His mother makes a pocket of her tail./And catches him. He clings—he clings—"

No children’s library is complete without Stellaluna, Janell Cannon’s gentle tale about learning to be yourself—even when you’re a fruit bat growing up in a bird’s nest.

A charming mix of bat science and children’s book culture, Brian Lies’ bestselling Bats at the Library is part of his picture book series about bats.

Every summer, Bracken Cave near San Antonio, Texas, is home to about 15 million Mexican free-tail bats, making it the biggest bat colony in the world. Here they are at dusk, leaving their pups in the cave—they pile them in clusters called creches—to hunt for bugs. Texas farmers are grateful that they will eat tons of cotton bollworth moths and army cut-worm moths every night. Bat Conservation International organizes trips to watch the bats feeding.

Bats are the best. (I’ve had them flying around my house though — not a big fan of that — but I still love bats!) Thanks for all the interesting info!

This is amazing! My daughter loves the picture book Amara and the Bats, so she really enjoyed looking at your pictures. So much great information here.