WE HUMANS HAVE HAD a love-hate thing going on with squirrels for a very long time.

Let’s start with the colonists. In the 1700s, squirrels were popular pets in upper-class households. Families would raid nests for kits then raise them by hand, housing them in tin cages. The squirrels were beloved for their cleverness, learning tricks and playing hide-and-seek with nuts. This is young Daniel Crommelin Verplanck (1762–1834), a New Yorker, at the Verplanck country home in Fishkill. Note the gold chain.

When the Industrial Revolution started to rev up, city leaders built parks for the salubrious effects of fresh air and sunshine, especially for the masses living cheek to jowl in tenements. Officials were firm believers that outdoor spaces helped to build moral character.

In 1847, park officials at Franklin Square in Philadelphia released a few Eastern gray squirrels, providing nest boxes and food in hopes they’d stay. These were, arguably, the very first city squirrels, selected in hopes they would “add beauty and interest to the parks,” says Etienne Benson, a professor at Penn who has studied the urbanization of squirrels. Boston and New Haven followed suit, and soon squirrels were chattering from the trees in parks everywhere.

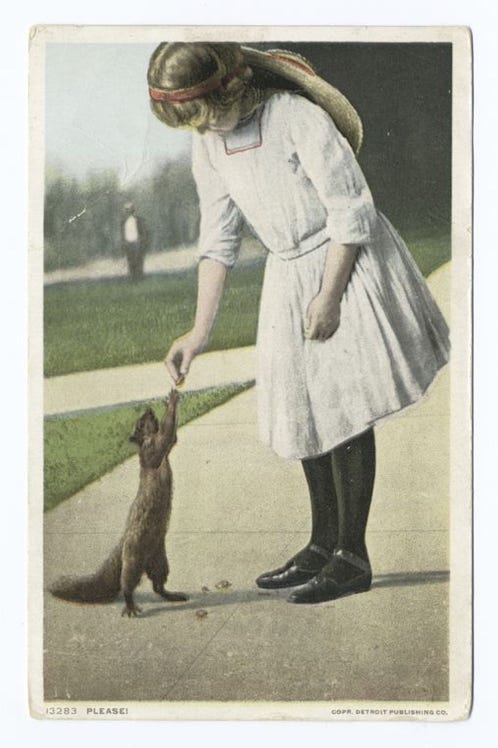

A second wave of squirrel releases followed in the 1870s. This time park-goers, especially children, were encouraged to feed wild squirrels “as a way of encouraging humane behavior,” says Benson, and to “cure them of their tendency toward cruelty.”

For a while, the fascination with city squirrels continued. Presidents Harding and Truman both had pet squirrels named Pete at the White House. And in the 1940s, Tommy Tucker, a male gray squirrel, became a media darling, touring the country with his owners to sell war bonds. At the height of his popularity, the Tommy Tucker Club had 30,000 members. Here’s Tommy wearing one of his 30 custom outfits. He dressed in girl’s clothes to more easily accommodate his tail.

As squirrels and humans lived in closer and closer proximity, the nation’s love affair with them began to wane. Residents complained that squirrels were either ruining the family picnic with their constant begging or ransacking the attic. “Squirrels are caught between unbridled admiration and relentless persecution, reflecting our contradictory relationships with animals,” says Nancy Lawson of The Humane Gardener. By the 1970s and the onset of the environmental movement, park leaders were discouraging residents from feeding squirrels, convinced that it was better for everyone if the squirrels were just left to their wild ways.

Country squirrels, all the while, were trying to stay a step ahead of predators—both animal and human. Hawks, coyotes, foxes, and bobcats are just a few animals who depend on squirrels for prey. And for millennia hunters have killed squirrels for fur and meat, a practice that continues today. (In Mississippi alone, two-and-a-half million squirrels are harvested for food every year.) Historically, many farming communities also placed bounties on squirrels who were getting into crops.

“Squirrels are caught between unbridled admiration and relentless persecution, reflecting our contradictory relationships with animals,” says Nancy Lawson of the Humane Gardener.

I DON’T THINK I’VE LIVED a single day without seeing a squirrel. I wake to the sound of them skittering along the peak of the roof. I hear their warning cry in the backyard and mistake it—once again—for a bluejay. My dogs line up at the window to watch them hang upside down from the bird feeder.

The name squirrel is from the Greek skiouros, meaning shadow-tailed—a tribute to their famously bushy tails. (“🎶 Gray squirrel, gray squirrel, shake your bushy tail…”) There are 268 squirrel species around the world. Here in Massachusetts, we have two tree squirrels (Eastern gray and American red); two flying squirrels (northern and southern); and two ground squirrels (chipmunks and groundhogs). It was news to me that chipmunks and groundhogs are in the squirrel family, too, but there it is.

I’ve spent the last month boning up on Eastern gray squirrels (sciurus carolinensis) which dominate my Western Mass neighborhood. I’ve loved them ever since my husband James and I raised four orphaned kits back in the 90s.

Gray squirrels are native to the Eastern and Midwestern U.S. and southern parts of Canada. Unfortunately, they were also intentionally introduced out West and in Britain, Ireland, Italy, and South Africa. In Europe especially, gray squirrels (or grey squirrels, as they’re known) are now outgunning the more delicate native red squirrels and are regarded as a pest that needs to be extirpated. In 2006 Britain launched a campaign to encourage restaurants to put gray squirrels on the menu: “Save a red, eat a gray!”

Except in the winter when they specially seek out midday warmth, gray squirrels are generally diurnal—active throughout the day. They spend almost all their time in trees—the Cirque de Soleil troupe of the canopy—leaping from tree branch to tree branch and rarely falling. Their defensive superpower, thanks to back feet that rotate 180 degrees, is the ability to descend headfirst down a tree trunk, which allows them to scout for predators.

Squirrels are, of course, nuts for nuts—their most vital food source. They are also omnivorous, eating insects, amphibians, bird eggs, fledglings, carrion, fruit, vegetables, flowers, and fungus. How they collect and store food, though, differs species to species. Gray squirrels are scatter-hoarders. Instead of caching one giant food stash, each gray will create as many as 2,000 small ones each year. To throw off any spies, they’ll even feign burying a nut then slip it into their mouth and bury it elsewhere.

This well-dispersed food strategy contributes to the gray squirrel’s amiable personality. If someone steals a nut, it’s no big deal, because there are plenty more to dig up. Grays will even share territories with other grays. Neighboring red squirrels, on the other hand, are small and fiercely territorial larder-hoarders. They have just a handful of stashes so they scream abjectly if threatened.

Studies at U.C. Berkeley were conducted to determine just how discerning squirrels are about nuts. The answer? Very. They roll each one in their paws to determine its value. How much effort should I put into this nut? Is it better to eat it now or should I bury it for later? A little later, or much later? And which pile is best?

Squirrels can remember where they left all that buried treasure because of their superior spatial memory—they use landmarks to imprint the locations of their stored food—and a great sense of smell. The few spots they forget or can’t sniff out become excellent candidates for sprouting trees—a critical piece of reforestation.

GOING NUTS LIVING WITH SQUIRRELS?

Squirrels are adorable except when they aren’t — like if they’re digging up your garden bulbs, or hogging the seed at your feeder, or nesting in your attic and chewing on wires. Here are two excellent trouble-shooting resources.

Nancy Lawson of The Humane Gardener encourages us to make an important mind shift with all animals, from “it’s either us or them” to “it’s us AND them.” Her book and website help us understand animal behavior and challenge our thinking. (A case in point: “How ironic is it that animals who help birds far more than any birdfeeder could are the object of such angst among birdwatchers and gardeners?”) She offers many less radical solutions for managing squirrel problems.

The Humane Society of America has an easy-to-navigate list of squirrel challenges and solutions, and is generally an excellent resource for learning to live peaceably with wild animals.THIS TIME OF YEAR, squirrels are frantically bulking up for the cold days ahead. (Maybe it’s why every fall so many of them are suddenly hurtling themselves in front of our cars.) They aren’t hibernators, so laying in the extra fat and amassing a food supply is critical to keeping them warm and energized through the winter. They have multiple homes, moving between nests built in tree cavities and dreys, those messy looking leaf-and-stick piles high up in trees. In the cold, they’ll spend most of their time in the cavities, where it’s warmer.

The first breeding season begins mid-winter, though most squirrels will only breed during the second cycle in May or June. Once pregnant, the females are on their own, typically giving birth to two to four kits. Mothers make a cooing muk-muk sound to soothe their babies and flick their tails and cry kuk-kuk to warn them of a threat. Squirrel milk is so rich, the tiny kits grow up in a flash, ready to be weaned by about eight weeks.

ONE SUMMER WEEKEND 30 years ago, I noticed a squirrel had been hit and killed in front of our house. The next day, as I walked our retired racing greyhound in the backyard, he stopped short and stared up into the trees, fixated.

Greyhounds are famously “keen,” meaning they are highly attuned to prey. I stared up too. Was that a squeak? Finally, I spotted them: four tiny squirrels clinging precariously to the trunk of a tree. The next thing I knew the first kit dropped 40 feet onto the lawn, taking an awful bounce. By then, James and the neighbors’ girls had joined us. We all ran around in circles trying to catch them as one kit after another fell to the ground. It would have been funny if it weren’t so horrible. We didn’t catch a single one.

We gathered the dazed and dehydrated squirrels into a cardboard box and called a wildlife rehabilitator. He was overwhelmed with rescued animals and asked us if we could raise the squirrels until they were ready to be weaned. He would then take over and begin the process of acclimating them to life in the wild. We agreed.

For the next three weeks, we kept the kits in a neighbor’s castoff guinea pig cage and fed them a special formula every three hours. I hauled the cage to work with me each day so we could stay on schedule. They behaved like kittens, mischievous and affectionate, climbing all over us then falling asleep in our laps. We were exhausted, but by then we were fully committed to Team Squirrel.

After three weeks, I drove the kits to the neighboring town where the rehabilitator was still working tirelessly, and handed them over. His first comment, which I still appreciate, was “Well now, aren’t they all plump and shiny?” 🐿️

SQUIRREL MARGINALIA

Gray squirrels are surprisingly good swimmers. They usually resort to crossing rivers and lakes when they are escaping predators or when food is scarce.

A number of towns and cities in Massachusetts have large populations of black and/or white squirrels. They are not species unto themselves. They’re gray squirrels with a genetic mutation that causes either excessive pigmentation (black squirrels) or minimal pigmentation (white squirrels).

During the pandemic lockdown, a trend took off—made popular on Facebook and Etsy—to build or buy miniature outdoor furniture for squirrels. Photographer Nancy Rose takes it one step further with her board book series called The Secret Life of Squirrels. She builds out elaborate miniature scenes in her Nova Scotia yard then captures on film the curious red squirrels who explore them.

A group of squirrels is called a scurry—which is what you get with Unlimited Squirrels—a book series for beginning readers by the inimitable Mo Willems. Fun facts include “A squirrel’s front teeth are sometimes tinted orange.”

The word sploot means to stretch out on your belly with your legs out in back, like many dogs do. On very hot days, squirrels like this little red one sploot, too.

From The Night So Bright A Squirrel Reads by Thomas Lux

The night so bright a squirrel reads

a novel on his branch

without clicking on his lamp.

Fabulous photo's! Thank you for sharing 😊

Love those pictures of you and James as temporary squirrel parents!