Three Cheers for Opossums!...Anyone?

Our nation's only marsupial deserves another look—and, thanks to wildlife rehabilitators, a second chance at life

WHEN I STARTED this urban wildlife newsletter last year, my old college pal Sara texted me this: “May I suggest one animal to discuss? The opossum. I have a visceral hatred for them, their color, their sickening tail, the nasty teeth, the creepy snout. I’d like to improve my attitude. Maybe you can help?”

It’s tough out there for homely animals. In a beauty contest judged by humans, opossums would score somewhere between the turkey vulture and the Norway rat. I appreciated Sara’s candor and her open mind, and resisted the urge to reply, But they let their babies ride piggyback!

So, this post goes out to Sara—and the many (many) people who share her reservations.

I’ve had little exposure to opossums. On the occasional evening walk, I see them tottering along in my Western Mass neighborhood. I also see them dead on the highway. A lot.

My only close-up was many years ago in Virginia when I was a girl staying on a horse farm. One day, doing chores, I turned the corner in the barn to find an opossum keeled over in the middle of the center aisle. I couldn’t imagine what killed it. Apprehensively, I picked it up with a shovel, carried it outside, and laid it next to the manure pile. Later that day, I told my friend about it, and we went back to look. The opossum was (surprise, no surprise) gone.

So last month, after doing some preliminary research, I decided to contact a wildlife rehabilitator. I knew opossums were frequent patients and thought, who would know better what might bring up their Q score?

FROM HER HOME AND YARD in Windham, New Hampshire, just over the Mass border, Frannie Greenberg rehabilitates more than 1,300 injured or orphaned mammals a year. She started the Millstone Wildlife Center, a non-profit, all-volunteer organization, in 2015 when the last of her three daughters left for college, proposing to her husband Michael that they take in six raccoons a year. “He likes to hold that over my head,” she tells me, laughing.

Judging by the enthusiasm on Millstone’s popular social media, their most charismatic patients are river otters, foxes, bobkittens, coyote pups, and—squee!—porcupettes. Frannie and her herd of volunteers, meanwhile, don’t discriminate. They give all wild mammals good medical care and a shot at getting back their freedom, including the ones most people put in the dime-a-dozen category, like deer mice, chipmunks, gray squirrels, cottontail rabbits, and opossums. Last year, Millstone took in a whole passel of opossums—182 to be exact.

“Opossums are wonderful, beautiful creatures,” Frannie tells me. “I hope more people will come to love them. They’re needed in our eco system—they’re nature’s cleaners, eating everything. Rodents, insects. They aren’t aggressive. And they’re our only marsupial!”

Millie the Opossum is a permanent resident at Millstone (try the link, Sara!). She’s two years old, which is ancient in opossum time, and has medical issues that make it impossible to survive on her own. She serves as an ambassador, participating in education programs.

When Frannie and I spoke a few weeks ago, Millstone also had a dozen other adult opossums in their care, all awaiting release after a long winter. Though recovered from their various injuries, they’ll have a better go of it in warmer weather, with more food at hand. Frannie was looking for wild places to relocate them, seeking property owners in New Hampshire who are amenable and—no surprise—don’t let dogs run loose on their land.

Once spring is in full throttle, Millstone will get many more opossum calls. “In any given year, we’ll see about 75% orphans and 25% injured adults,” says Frannie. “More people know now to stop and check to see if a dead opossum has babies, so more are being rescued.” Most of their moms have been killed by dogs or hit by cars. (Their slow footedness and appetite for roadkill often make them roadkill themselves.) Good Samaritans find young joeys in the mother’s pouch, or—if they’re older—clinging to their mother’s back or flung nearby.

In rehab, the smallest joeys go into an incubator where they’re given feeding tubes until they can move on to drinking from bowls. The older orphans get opportunities to scavenge, climb, and learn the basics, like night versus day, rain versus sun—experiences and skills they would have learned from their mothers. (I’ve watched this video from Millstone dozens of time. Sound up!) When they reach about two pounds or 12 inches long, they’re ready to be released.

“Opossums do well in rehab,” explains Frannie. “They’re not snugglers. You can release them, and they won’t run up to humans. They’re very food motivated.”

As well as being a licensed rehabilitator, Frannie has had a long career as a wildlife educator, and her perspective is clearly “to understand an animal is to love that animal.” As I discovered over the last month, everything I understood about opossums could fit in one of their little paws. I had a lot to learn and maybe even more to unlearn.

Wear gloves. Keep the animal warm in a dark, quiet place. Don’t give them food or water. In addition to providing care to animals, rehabbers share a wealth of knowledge with those of us who are facing a wildlife emergency but clueless about what to do. Millstone’s site walks us through the steps to take if we find an animal who is injured or orphaned (be sure!). If you don’t know a rehabilitator in your state, Animal Help Now provides contacts, an app, and scads of information.THERE ARE more than 100 opossum species waddling around the world today. Despite what we may have heard, opossums aren’t related to rats, which are (like us) placental mammals. Opossums are closer to their marsupial cousins, kangaroos and koalas, who also raise their babies in pouches. Over the last 65 million years, give or take, opossums and other marsupials, once dominant, were outcompeted by placental mammals, which now make up 90% of all mammals living today.

Our opossum—the Virginia opossum (didelphis virginiana)—made its evolutionary way to North America 3 million years ago thanks to the Great American Interchange, a geological event that connected North and South America via the Isthmus of Panama. The first written record we have of an opossum is from Captain John Smith, the English colonist from Jamestown, in 1608:

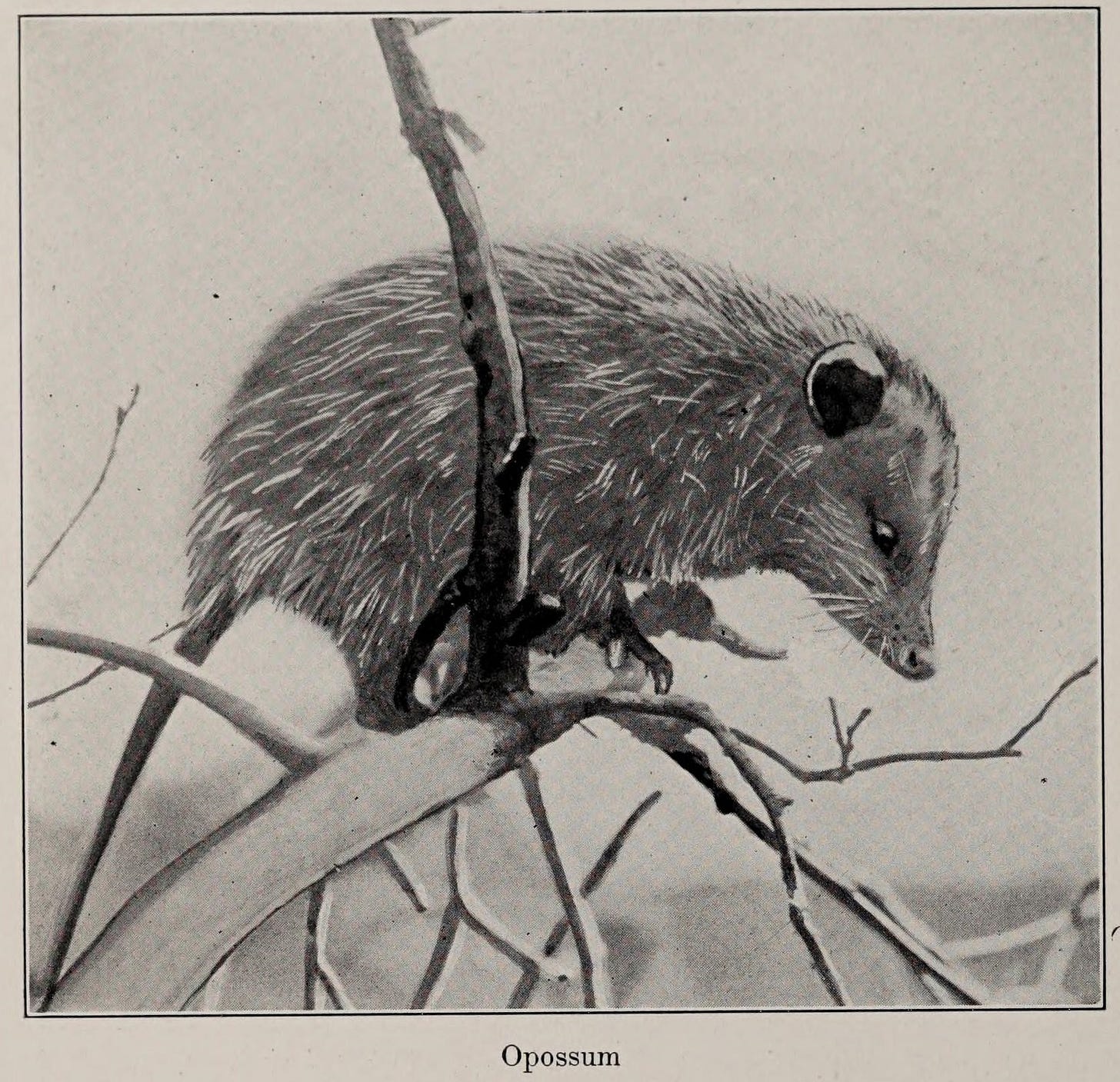

An Opassom hath an head like a Swine, and a taile like a Rat, and is of the bigness of a cat. Under her belly she hath a bagge, wherein she lodgeth, carrieth, and sucketh her young.

Opossums likely got their name from the Algonquian “apasum,” meaning “white animal.” Though many people in the U.S. use opossum and possum interchangeably, it’s not technically correct. Possums are from a different order of marsupials who live in Australia and New Guinea.

Culturally, opossums are heavily identified with the south, where they have been a mainstay, with a side of sweet potatoes, for centuries. In Synopsis of the Mammals of North America and the Adjacent Seas, published in 1901, Daniel G. Elliot described their range as running “from New York on the Atlantic Coast to Florida and west to Mississippi and Texas.” By the 1950s, though, opossums had spread out north and west, over much of the country, including into New England.

For perspective, when my Northampton house was built sometime in the 1870s, there wasn’t an opossum to be found in the state. Today, they are abundant in every mainland town in the Commonwealth.

The opossums’ ability to adapt to, and take advantage of, human habitats has allowed them to succeed and fan out. They’re omnivores and roamers, opportunists and scavengers, making do with what they find. A shed to hide under. An overflowing trash can to root through. They’re excellent climbers and swimmers, too. We’ve helped, as well, by extirpating many of their predators. Still, our northern frontier isn’t always easy for opossums, who are ill-suited for cold winters. They’re loners, with no nestmates, and not enough fat to allow them to hibernate. As Frannie can attest, they tend to get frostbite, especially on their hairless ears, tails, and paws.

THERE’S A LONG-HELD opossum myth (among many) that they deliver their newborn babies by sneezing them out their nose. As far as this placental mammal is concerned, the reality is only slightly less otherworldly.

(You might want to skip this part, Sara.)

Male and female opossums are called jacks and jills. The jacks have a two-pronged penis while the jills have two vaginal canals and two uteri. Even the sperm come in pairs. Evolution, after all, is about increasing the odds. Jacks and jills have a pretty transactional relationship. Starting in late winter, they’ll breed two or three times a year, depending on resources, and then go their separate ways.

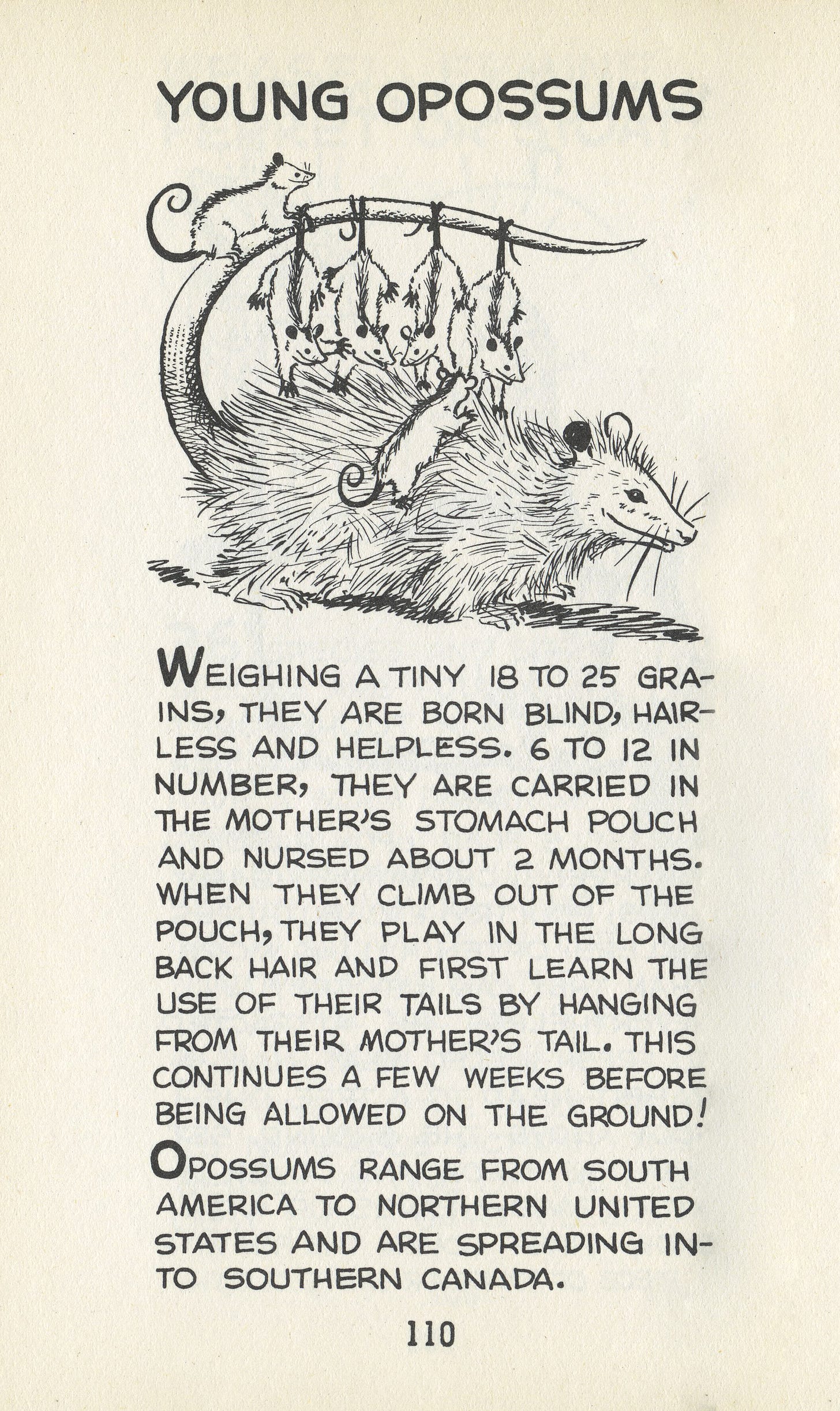

Just 12 days after breeding, the jill will give birth to embryonic-like joeys: blind, naked, semi-transparent, each smaller than a jellybean. There may be as many as 20 in a litter. Because the mom has only 13 teats, newborns must immediately crawl as fast as they can across their mother’s belly to try to get into the pouch and claim a nipple. The lucky ones will remain latched, sequestered safely in the pouch. The rest don’t make it.

After about 10 weeks, that pouch starts to get really crowded. The joeys venture out, all clinging to their mother’s back. (The sight of an opossum carrying her babies always reminds me of the catbus in Miyazaki’s My Neighbor Totoro.) These forays keep the joeys safe, of course, but they also provide lifesaving lessons in foraging, finding shelter, and recognizing predators. (And lessons for us humans in maternal patience and fortitude.) Once they’re weaned, the joeys will test their own independence until they finally go it alone at about five months. In only a few months, they’ll be ready to breed themselves, starting the cycle all over.

THOUGH THEY GENERALLY get little respect, or worse, opossums make good neighbors. Unlike the urban wildlife they’re associated with—like skunks and raccoons—opossums very rarely carry rabies, probably because their naturally low body temperature isn’t hospitable for the virus. Their paws are too delicate for serious digging or scratching so they don’t mess up gardens or damage buildings. Nursing mothers might spend a few weeks in one spot, but otherwise opossums are nomads, moving on every couple of days.

Ecologists, eager to give opossums some good PR, call them “nature’s janitors” because they’ll eat things most others don’t, like carrion and rotten fruit. They also eat things we generally don’t want around our homes, like mice, rats, slugs, snails, and scores of insects (including ticks, though the numbers they consume are up for debate). If you have chickens, keep a tight coop, since opossums have a thing for eggs. If you have horses, lock down your grain and feed. Horses can pick up a parasite from opossum feces that cause equine protozoal myeloencephalitis.

Opossums will beat a hasty retreat if they see you. Follow them, and they’ll hiss and flash their 50 teeth in hopes of scaring you off. (Adorably, the joeys do this, too.) Corner them, and they’ll “play possum.” It’s a misnomer, really, since the response—called tonic immobility—is entirely involuntary, an evolutionary adaptation equivalent to a Hail Mary Pass. Here's what happens.

Coyotes, dogs, bobcats, owls, and other raptors predate opossums. Under intense stress, opossums will faint, collapsing on their sides, drooling, excreting a foul odor, and remaining, for minutes or hours, in a catatonic state. It’s not an appetizing look. Because most predators are conditioned to eat live prey, they’ll usually move on. When the coast is clear, the opossum’s ears will give a little twitch, then he’ll get up and go on his way.

I’ve tried many times to imagine why the opossum I found in the barn all those years ago was in that state, too. My only theory is that the farm’s two Dalmatians, who roamed the place, might have been up to no good shortly before I arrived.

BEFORE I CLOSE, a word about that tail.

We humans, furless and tailless as we are, like our woodland animals fluffy, especially their tails. Gray squirrels have bushy tails that curl, rabbits have pompoms, the red fox has a black tail that looks dipped in white paint. Opossums have long, bald tails that stick out straight when they walk. “Some people equate them with rats,” says Frannie.

Thanks to those prehensile tails, though, opossums are arboreal wonders, climbing, grasping, balancing like an acrobat. Virtually unshakeable. Made almost entirely of muscle—plus hairless for a better grip—the tails operate like a fifth limb, helping opossums navigate from branch to branch, escaping a predator, or reaching a crabapple, or finding a small cavity to hide in. On the ground, adults use them to gather leaves (please look!) in their curled tails and build a comfortable nest. Joeys, meantime, need their tails so they can stay attached to their mother during her roamings.

I’d like to heed Millstone’s “animals we understand are animals we love” approach and reframe how we might think. What opossums’ tails might lack in beauty they make up for in design. Kind of like opossums themselves.

And design is its own beautiful thing.

MARGINALIA

The opossums who live all along the West Coast and into British Columbia are not native. Starting in the 1800s, Easterners transported them west, hoping to raise them for food or fur, keep them as pets, or release and hunt them. Between escapes and releases, the opossums flourished. Most biologists don’t consider them a major issue because they’re generalists, who eat widely and don’t pose risks to specific native plants or animals.

Opossums love to eat snakes and possess a magical peptide that allows them to survive poisonous bites from rattlesnakes, copperheads, and moccasins, among others. Scientists are studying this in hopes of developing less expensive anti-venoms for humans.

Western Mass artist and author Diane DeGroat has a bestselling series about Gilbert, a bespectacled opossum, and his animal friends. “Opossums aren’t too brave and they’re not too timid. I think they are the kind of animals that things just happen to,” says DeGroat. “And that's what Gilbert is like.”

Leave it to Margaret Renkl to write with such heart about wildlife rehabilitators. (Gift link.)

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Thank you to Frannie Greenberg, Lindsey Shaklee, and Denise Sweeny at Millstone for their help with this post and for the yeoman’s work that they do rehabilitating mammals. A big thanks to Sara, too, for her curious nature (and curiosity about nature).

Three cheers indeed! Opossums may not win beauty contests, but they totally win at being awesome. This piece gave me a whole new level of appreciation—and a few “aww” moments too. 🫶

Terrific! I so look forward to your essays, and this might be favorite yet. You make strange animals less strange, and let us see the perfect logic of their wildness. The strangest thing is often our own strange response to such wildness.