Where Frogs Go a Courtin'

A series of landscaping decisions give our local frogs a little lift

THIS IS A STORY about frogs and gardens. And frogs and gardeners.

Smith College, a short walk from our house in Northampton, Mass, is my favorite destination on warm nights because of its cacophony of frogs. In 1891, when the college was 20 years old, its trustees hired Frederick Law Olmsted, of Central Park and the Boston parks system fame, to reimagine the campus as an arboretum. His relationship with the trustees fell apart before he could fully implement his vision, but much of his trademark design still defines Smith today. It’s got a pastoral feel, a way of unfolding, with naturalistic, curving lines and enormous specimen trees. Paradise Pond, which colonists built in the late 1600s by damming the Mill River, serves as both the real and symbolic heart of the campus. Soon after its Olmsted period, Smith added formal gardens and a Victorian conservatory.

For more than a century, the campus has been heaven for botanists—and for frogs. Today gray treefrogs hide in the treetops above Paradise Pond while a small garden pond by the greenhouses teems with bullfrogs, pickerel frogs, and—plunking like banjo strings—green frogs.

It’s not easy being a frog, to almost quote Kermit. In recent decades, their habitats have shrunk alarmingly, along with their populations. They’re sensitive to pollution, pesticides, disease, and the disruptions of climate change. Every landscaping and garden decision we make, big and small, has profound effects, for better or for worse, on their ability to survive in cities and towns.

TO JUDGE BY ITS NIGHT SOUNDS, my own neighborhood, with its residential lots made up of patios, lawns, and gardens, did not historically support a lot of frogs. Over the years I heard spring peepers in April as I neared wetlands at the end of the next street. Sometimes I’d find toads, but never frogs, in my garden. Then came last spring.

Out on a dog walk one night, I heard an unfamiliar call from behind the tall hedges of the house on the corner. First it was one, then two, then three. As the nights passed, it became a chorus. Know them? Male gray treefrogs call out a beseeching, high-pitched trill, over and over, every night, for up to four hours. Known as an advertisement call, it’s a male frog’s version of “For Pete’s sake, come mate with me, pleeeease.”

I started going out after dark just to stand on the sidewalk and listen to their calls, which were interrupted only by the occasional modest gunk! of a green frog or the rum of a bullfrog. Frog vocalizations are pure comedy, yes, but to me, they’re also music—the sound of a healthy ecosystem. I knew the house had new owners, and I had a hunch.

Last month I introduced myself. Lisa and Mike Kelso are retired architects from Hawaii. Several years ago, during the throws of the pandemic, they decided to move back to the East Coast and started researching towns and cities with walkable neighborhoods and easy access to wild spaces. Northampton checked all the boxes. They bought their house on our street sight unseen, then undertook a major renovation, working remotely with a contractor. “We never even laid eyes on the house until the day we moved in,” said Lisa. It was perfect. The sunny backyard had a long stretch of lawn bordered by trees and towering evergreen hedges.

Listen to frog calls across an entire season—in 22 seconds!—at Hilltown Families. The study of natural cycles like this is called phenology.Today the Kelsos’ backyard is a sprawling perennial garden with winding stone walkways, a few shade trees, and—true to my hunch—two new manmade ponds. Small, with no fish (koi or otherwise), they’re filled with aquatic plants and ringed with irises. When I visited, the whole place was thrumming with activity. Squirrels chased each other in spirals up trees while dozens of birds took impatient turns at feeders suspended 8 feet above the garden. (Not coincidentally, a tall black bear stands at seven feet). Green frogs popped their heads out from under blooming lily pads, blinking one eye at a time.

Lisa chose a local landscape designer, Owen Wormser, to help her re-envision the yard. She wanted a perennial garden, with lots of color, plants for pollinators, and a lotus pond. His first question surprised her. “Do you have to have grass?” She paused and thought, Maybe not?

Owen, who is known for his sustainable garden designs, set to work, creating different layers of color and interest that would work year-round—and that included attracting wildlife. Water is delightful, of course, appealing to all our senses, but it also draws animals. In the end, he selected dozens of pollinator-friendly plants and built two ponds: one lotus, the other a bigger pond fed by a small river. “I personally feel,” says Owen, “that good design—of any sort—takes into account the community of all living things.”

Green frogs started showing up in August 2022, only a week after Owen installed the ponds. Lisa and I wondered together how they even knew the ponds were there. The answer, I’ve since learned, is that frogs wander. They’ve been tracked hopping more than a mile in search of a better place for clean water, food, and shelter. The Kelsos had delivered the trifecta.

You can help frogs by providing fresh water, gardening organically, and growing native plants, which attract the insects they rely on. If you have a pool or fountain, provide an exit ramp so frogs can escape. If you must pick up a frog (to move it to safety, for example), you have to protect its sensitive skin. Be sure to either wash your hands well or, a last resort, rub your palms and fingers first with soil.Sometime early the next spring, Lisa and Mike started hearing the first gray treefrogs. “Each night starts with just one,” says Lisa, gesturing toward a tall Kentucky coffee bean tree, “chirping from the top of that tree.” By dark, the yard turns into more of a contest, each male trying to out-croak the other.

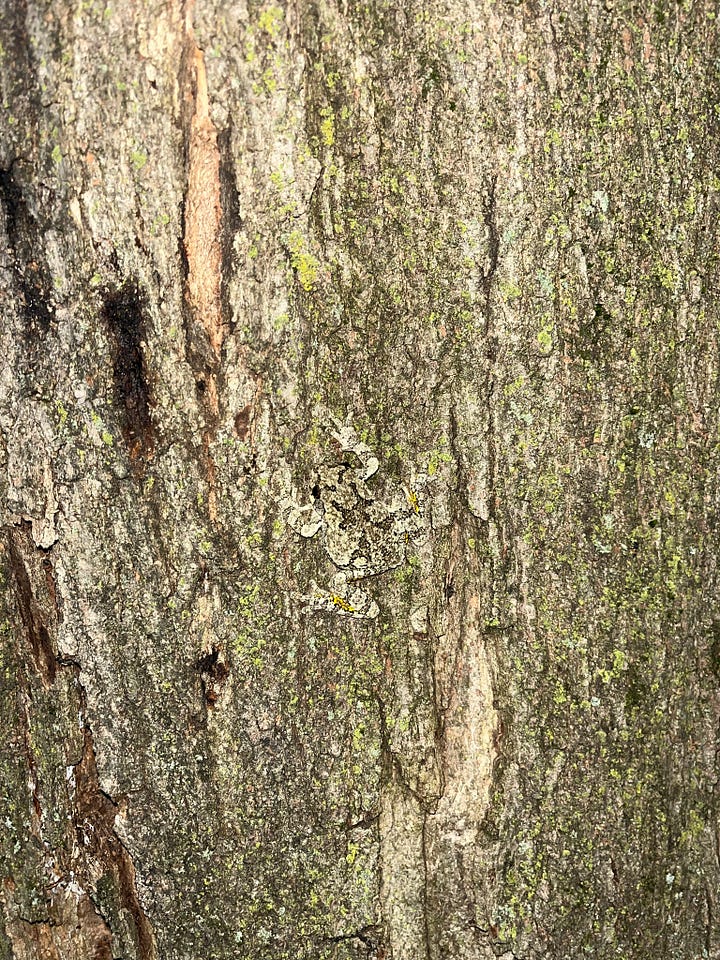

I’VE FALLEN HARD for gray treefrogs even though I’ve never actually seen one. Neither have Lisa and Mike. Hyla versicolor—which means “variable color”—are masters of camouflage. They change from bright green to brown to gray, with toad-like skin that blends in with bark, lichen, stone, moss, and leaves. They are wide ranging—found in more than half the country—and clock in at one to two inches in length, only a hair bigger than a spring peeper. That makes them conveniently snack-sized for many meat eaters. Fortunately, they’ve also cleverly evolved.

Gray treefrogs secrete a bitter-tasting irritant through their skin to discourage predators. They also sport orange or yellow bands on the inside of their back legs. In many parts of the animal kingdom, neon colors = poison. (Think poison dart frogs.) So it’s likely gray treefrogs flash these colors as a “warning” when they’re being chased. Aposematic coloration is the name of this adaption. Some brightly colored animals are actually toxic, while other geniuses just look like they are.

A sticky fluid in the gray treefrogs’ toe pads allows them to climb trees nimbly and perform high-flying gymnastics to catch moths, spiders, ants, and beetles. When winter approaches, they bury themselves in the forest floor and—through a complex system that includes producing anti-freeze—turn to frogsicles. They can go months in that state without having a heartbeat or taking a breath. When spring arrives, they thaw out and hop away.

Until recently, herpetologists believed that the gray treefrog and Cope’s gray treefrog, which is found mostly in the Southeast, were the same species. Strangely, the two species’ only significant difference is genetic. The Cope’s gray treefrog is a diploid (24 chromosomes) while the gray treefrog is a tetraploid (48 chromosomes). They interbreed, though rarely successfully.When a gray treefrog male finally gets the go-head, he needs fresh water to mate. Ideally, that’s a fish-free pond, like at the Kelsos’, or a swamp, vernal pool, or flooded ditch. In a pinch, gray treefrogs will even lay eggs in rainwater-filled swimming pool covers or working fountains. When his mate is ready, he hugs her from behind as they float together on the surface of water—a position called amplexus. This stimulates her to release thousands of eggs in bunches of small, jellied masses. He quickly fertilizes them with sperm.

Then the clock starts ticking. The eggs take a week to hatch into tadpoles, then the tadpoles take two more months to metamorphose into froglets. Along the way, most of them don’t make it. They get picked off by dragonflies and herons and overzealous science teachers, and anyone else who happens by.

WHICH BRINGS me back to Smith.

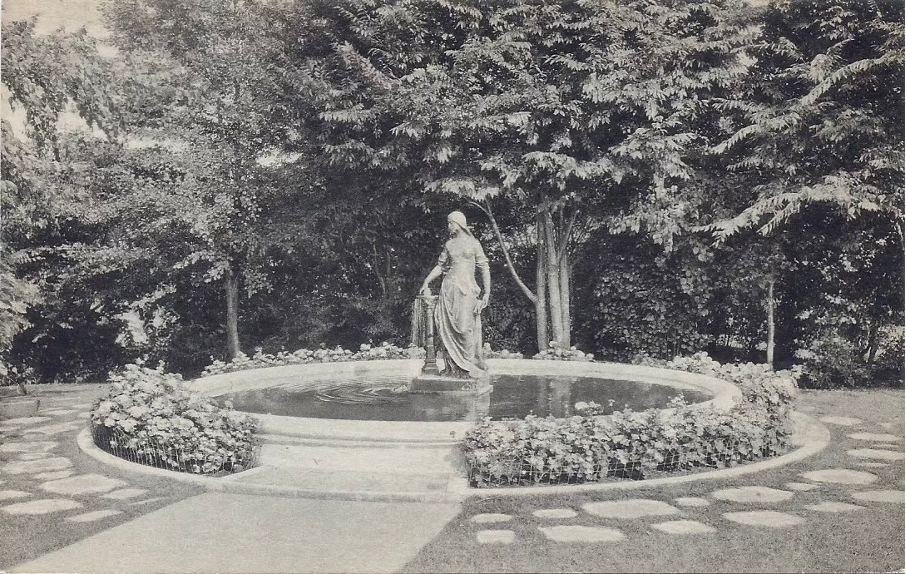

A frog’s hop away from the greenhouses and their little pond is Lanning Fountain, an affecting memorial to a Nebraska student who died in 1910 when she was just a junior. The bronze sculpture, modeled after work by the French sculptor Jean Gautherin, is of a life-sized girl. The fountain’s base is low and wide, surrounded on one side by hostas. They’re a good place to hide if you’re green and an inch long.

Through many springs, students and locals like me would watch the fountain fill up with egg masses. Slowly, hundreds, if not thousands, of tadpoles would hatch. As the weeks passed and the tadpoles fully transformed, some of the froglets—little frogs with tails—would struggle to make it over the basin’s edge. On a few nights I met like-minded strangers there who, like me, would bring a flashlight and look for worn out frogs clinging to the dry lip and ferry them a few feet to the hostas.

Lanning Fountain is an important emotional touchstone for Smith’s students and alums, and a constant reminder to all of us of how fragile life can be. A few years ago, the pumps stopped working, and the fountain went dry. The college recently posted a sign that says “Coming soon! Lanning Fountain restoration.” I’m hoping it will be full and flowing by May, when, from the tops of the neighboring trees, the sanguine trilling of gray treefrogs will begin to sound again.

FROG MARGINALIA

This iced over garden ornament, identified on social media as a real frozen frog, went viral a few years ago.

The ultimate buddy story, Arnold Lobel’s Frog and Toad early reader series has stolen hearts for more than 50 years. From the collection of The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, MA. Arnold Lobel, Illustration for Frog and Toad All Year (HarperCollins). Gift of Adrianne and Adam Lobel (The Estate of Arnold Lobel). © 1976 Arnold Lobel.

Mr. Toad from Wind in the Willows emerges from Toad Hall ready to drive. This 1931 illustration, “Swaggering down the Steps,” is by E. H. Shepard, the illustrator of the Winnie-the-Pooh series. It sold at auction in England two years ago for £33,644.

Remember One Froggy Evening?

Many of the photos here are from iNaturalist, a massive international community science project in which professional and amateur naturalists record their observations. There are 30,903 entries for gray treefrogs, and counting.

And a Red Fox PS:

Thank you for the many fun replies I got to this post. I loved your fox stories. One, from my friend Penny, made me laugh: “The foxes in London make that crazy screeching at night. When I first moved into the cottage, a fox would leave me piles of welcome poop on the mat outside the door.” (Foxes like to defecate on top of things to mark their territory.) Cheerio!

Alix -- this is so great! We hear frogs a lot near our house, and this really helped me better identify who's talking. I love how lovingly you talk about these wonderful creatures.